News

Creative Conversations: Pekka and Teija Isorättyä

Artist family Teija, Pekka and Iisakki Isorättyä work and travel around the world. Currently, they reside in Brooklyn, preparing their solo show at Ierimonti Gallery.

Pier 6, from which we are about to take the East River ferry to Dumbo, is a recently reconfigured public space on the Brooklyn waterfront, with extensive green spaces planted with native plants and a variety of playgrounds. Why is Pier 6 a place of special significance for the artist family Isorättyä?

This place attracts us for multiple reasons. We live close-by, and almost every time we leave the house, we intuitively start walking towards the waterfront. We enjoy the open river space, the many parks - Pier 6 has the coolest playgrounds for kids - and the view towards Southern Manhattan. Watching the Manhattan skyscrapers and the boats on the East River feels almost like watching a mountain view: it’s calming in the same manner. The streets look like canyons. And the ferry deck is the best place to observe the city architecture and the bridges over the East River.

So the river offers a merging point between the urban and the natural landscapes. But the piers also possess a border-like character that you find inspiring.

We have always found places that are in-between very inspiring and comfortable. This waterfront is on the border of residential and industrial neighborhoods, and it is also the border between Brooklyn and Manhattan, and the border between America and the Atlantic Ocean. A border is always interesting, no matter what kind of border it is; the beginning and the end of a situation are fascinating because all the action is happening in-between. Maybe you feel freer because you are in-between, because you are not here anymore but, at the same time, you are not there yet. It is like the moment when something good is about to happen. Like A. A. Milne says in Winnie the Pooh: “Although eating honey was a very good thing to do, there was a moment just before you began to eat it which was better than when you were, but he (Winnie the Pooh) didn't know what it was called.”

Do you think that the New York landscape affects your work?

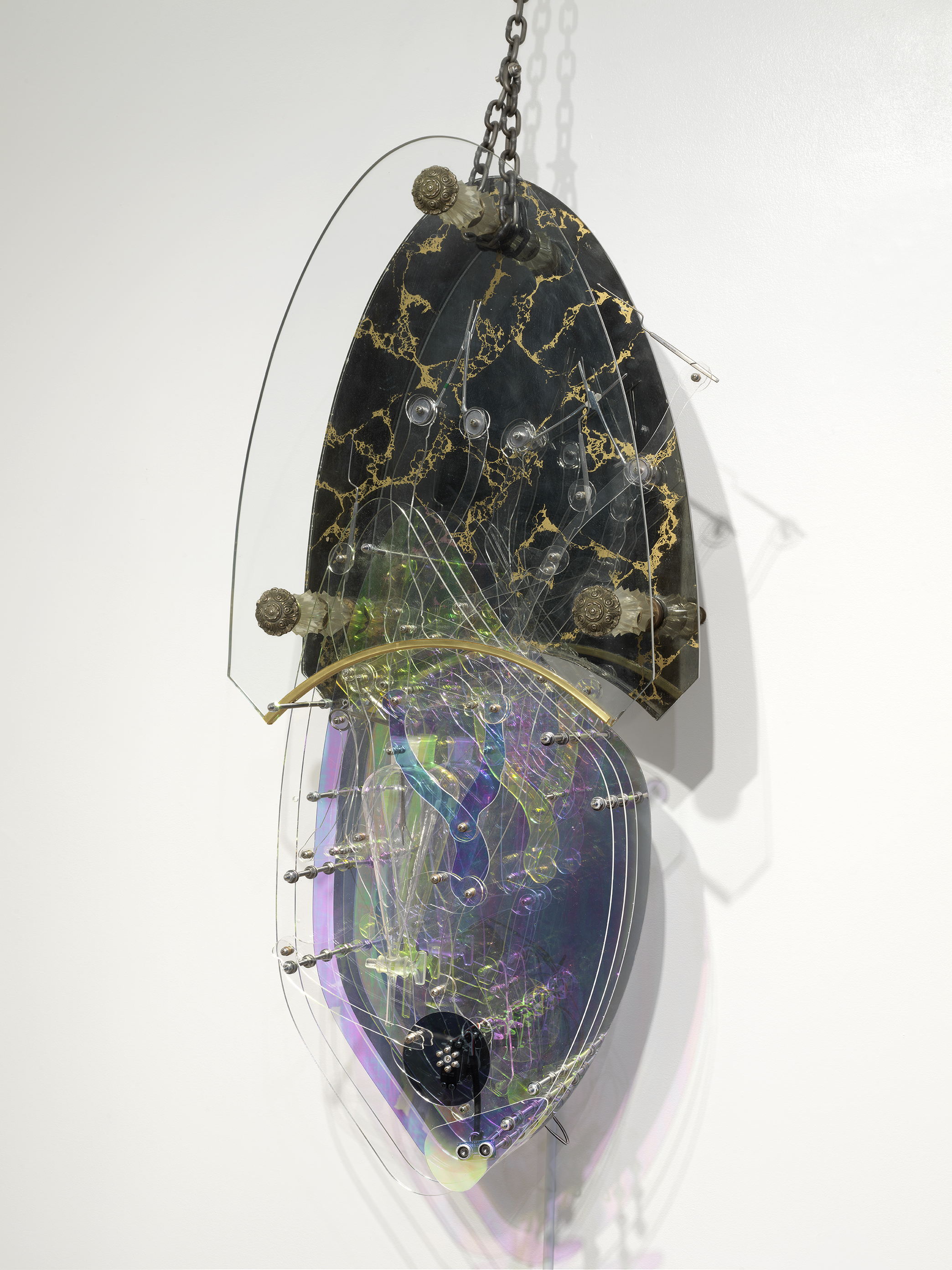

We are working with very shiny materials at the moment, which might be because of the reflective silhouette of Manhattan, or the overall glamorous feeling of the city. Alongside smooth, irradiating acrylic sheets, we use coarser, rough materials that we find and encounter by chance, for example on the streets. Such materials have a history and carry symbolic references to actions that have happened in the past or that might happen in the future.

Since last year we have also used surgical hospital equipment, stainless steel objects, and instruments in our installations. We got the tools as a donation from a Finnish hospital that was updating its equipment.

Some of the new materials we work with we have just recently discovered here in New York. Our friend Myles Mangino works as a light engineer for a band called The Pixies, and he took us to search for cool stuff from old warehouses he knows in Long Island City. One of them, a sound and lighting rental company called The See Factory was throwing out some old equipment. We found these objects very interesting. We started to remove the lenses and irises from some old stage lights and began to imagine what kind of stars and shows the lenses had seen.

And in your art, you give a new life to those objects that otherwise would have been destroyed.

We think that collectively we are experiencing an era of fundamental change because of the current, rapid technological and digital changes in society. And because as artists we are always looking for objects with stories, we are often right on the clashing point of old and new. Maybe you can also see our work as a humans’ struggle to reinvent themselves to meet the current standards.

How about Jane’s Carousel, the famous merry-go-round in Dumbo, where we are going to finish our walk? You mentioned that it is also one of your favorite places in New York.

Our fascination with Jane’s Carousel is part of our long-standing fascination with mechanical objects. The merry-go-round was very beautifully constructed almost 100 years ago. It has been conserved very carefully and placed inside a glass pavilion next to the massive pillars of the Brooklyn Bridge. We built our first mechanic installation together in 2006, and since then we have observed and studied all kinds of mechanical devices with great pleasure.

Are there some other places or things that have inspired you lately?

Nowadays we enjoy places where we can find a common interest as a family: places and things that have cultural depth or a history, but also room for play. As a family we enjoy things on multiple levels: things that are simple or attractive enough to spark the interest of a two-year-old, but which are also interesting for adults. During this conversation, you told us about pinball machines that were dumped in the East River during the prohibition in the 1920’s. That could be an excellent source of inspiration and adventure. To find them, dive them up, and rebuild them as art pieces.

Our son Iisakki’s daily play and the way he partakes in our projects is a constant inspiration to us. He is now making videos of his own. In one video we visited a toy store with Iisakki having a go-pro camera on his head. His reactions and impulses are so immediate; you can see what he thinks by watching the video. The point was to change the point-of-view and the creator. Many times conversations are the most significant inspiration for us. The hardest part with all inspiration is to keep what is relevant to you, filter out the rest, and to be honest with yourself.

Your solo show Binary Operations is opening at Ierimonti Gallery on Lower East Side, New York on April 5. Is it going to include some new themes that you haven’t explored before?

In this show, we are concentrating on reflections, and how they are born and multiplied on spliced mirrors, sounds, and repetitions of the mechanics. We are trying to make images of our times. These sculptures are becoming quite abstract, digitally controlled fragments which seek to evoke both terror and relief, to show the fear but also bring hope for the future. And of course, they are attractive for kids.

Interview by Liisa Jokinen